connecting the dots;

The walking purchase of 1737 is a route which entailed howertown road in northampton county pa USA. after walking briskly during the competition to win 500 acres, they pit stopped after 44 miles from wrightsown pa on my front yard,(IN MY OPINION VIA RECENT NEWS_FAKE ) which is on 3324 howertown road.peak summit-great view= no question- this was lynford Lardner FOB. forward operating base here in the hinterland. This leads to Stenton massacre 1763 and Paxton boys- eventual expulsion of all native in the area- even the Christian converts.

|  Jun 28 (2 days ago) Jun 28 (2 days ago) |   | ||

Dear Mr. Azar:

The State Historic Preservation Office forwarded your inquiry regarding the land warrant tracts in your neighborhood to the Pennsylvania State Archives for action. Attached is a copy of Map #8 from Chidsey’s The Penn Patents in the Forks of the Delaware showing the eighteenth-century disposition of land in your area. We suspect that your property would fall in the square containing the John and James Allison tracts located near the middle of the map. That is the same parcel as Tract “D” in the inset, which was patented to Lynford Lardner on November 1, 1742 (Patent Book A-11, page 16). If you would like to study the Penn Patents book more carefully, you should find a copy at the Northampton County Historical and Genealogical Society in Easton (see: https://sigalmuseum.org/

To learn more about the Lardner warrant and patent, you may wish to request research in the state land records—warrants, surveys and patents. Use the Land Records Order Form on our website (see: http://www.phmc.pa.gov/

For transactions after the Lardner patent, check the Bucks County and Northampton County deeds.

We wish you success with your research. Feel free to contact me at the e-mail address or telephone number below if you have further questions about state land records.

Sincerely,

Jonathan R. Stayer

Supervisor of Reference Services

Pennsylvania State Archives

350 North Street

Harrisburg, PA 17120-0090

(717) 783-2669

Lynford Lardner is a dashing gentlemen. my father once said this property is a gentlemen place- he was so right.

also, Lynford ran the dance assemblies, wonderful, i heard the continental marines got their uniform from this style. semper fi- ha in french yet.

History's Headlines: Drums along the Lehigh: 250 years ago troubles between Indians and Whites boiled over into violence at John Stentson's Frontier Tavern in Northampton County

Fought on battlefields in Europe, America, Africa and Asia, it turned Canada and much of France's overseas empire over to England. Britain's victory also set the stage for the American Revolution and the creation of the United States. But that was still in the future.

Far from the silken cushions of the Pompadour's Versailles boudoir, the Pennsylvania frontier smoldered in anger and resentment. Native American tribes, who in 1758 had signed a treaty in Easton (a copy of which is on display in the Northampton County Historical and Genealogical Society's Sigal Museum), switching their allegiance from France to Britain- a move that had assured the victors of their victory- felt betrayed.

The promises of better trade goods and regular supplies of gunpowder, which the Native Americans needed for hunting, were going unfulfilled. And despite British pledges, colonists were taking more and more of their land. With the French gone they went from being a valued ally of Britain to a subject people.

A French army officer, Captain Louis Antoine de Bougainville, knew from experience it could be fatal to anger the Indians, especially for frontier settlers. "What can one do against invisible enemies who strike and flee with the rapidity of light?" he wrote in his journal. "It is the destroying angel."

With all these factors in play it should have surprised no one when warfare broke out in western Pennsylvania in May, 1763. It would run until late 1764, leaving eight forts destroyed and hundreds of colonists killed or captured. Its most prominent figure was the Ottawa chief Pontiac, thus history has given it the name Pontiac's War.

Mrs. Stenton, for unknown reasons, took offense at the Indians' presence. Moravian missionary Rev. John Heckewelder, who claimed to have spoken to one of those Indians many years later, described the encounter this way:

"The landlord not being at home, his wife took the liberty of encouraging the people who frequented her house for the sake of drinking, to abuse those Indians, adding that she would ‘freely give a gallon of rum to any one of them that would kill one of these black devils.'"

Throughout that night the Indians, who understood English, heard people coming in and out making threats against them. And the next morning they discovered that some of their most valued trade goods were missing.

When the Indians complained they were told to leave. Returning with a legal document from a local magistrate ordering that their goods be restored to them, the Indians were told again if they valued their lives they would leave, which they did. But in the quiet of their village they laid plans.

On October 8, 1763, the destroying angels visited Stenton's tavern again. A group of local militia was there, commanded by a Captain Jacob Wetterholt. Early that morning Wetterholt asked his servant to get his horse. On opening the door the man was shot dead. Another shot mortally wounded Wetterholt. A sergeant was also wounded.

An Indian spotted John Stenton as he was getting out of bed and shot him. According to a contemporary account he was able to escape and run a mile before he dropped dead from loss of blood. His wife and children were safe in the basement.

Though wounded, Wetterholt was able to shoot through a window at an Indian attempting to set the tavern on fire, killing him. With that the Indians fled. Over the rest of the day at least 23 local people, who had nothing to do with Stenton's actions against them, would be killed by the Native Americans before they left the region. Wetterholt was taken to Bethlehem's Crown Inn where he later died.

The Indian raids threw the Lehigh Valley into chaos. Fearful farmers and their families were convinced that they were about to see a repeat of the French and Indian War. They flocked into Allentown, disrupting the service being held at a log church located where Lehigh County's parking garage is today. Bethlehem was also besieged by refugees.

Calls were made to Governor James Hamilton and he ordered 800 militia troops raised. But it was all for naught, for the Indians never returned. And apparently no one thought it was worthwhile to chase them. The Valley's Indian "troubles" were over.

The events did help fuel a reaction by settlers in the western part of Pennsylvania who were known as the Paxton boys. That December, they massacred some peaceful Christian Indians in Conestoga jail where they had sought protection. They based their action on testimony by Mrs. Stenton that a Moravian Indian, Renatus from Bethlehem, had plotted the attack on the inn. Renatus was later tried and released.

Only the actions of Benjamin Franklin kept the Paxton Boys from trying the same thing in Philadelphia. "If one Indian injures me, does it follow that I may revenge that injury on all Indians?" he asked them. Franklin's question was to haunt relations between whites and Indians until the official end of the frontier 130 years later

in 1893.

END OF LOCAL NEWS STORY::::::::::::

My son and his friends train for long distance endurance, edward marshall and the other runners/walkers were innocent men participating in the fake new corruption of rich people playing games. I WANT TO KNOW EXACTLY WHERE THE PIT STOP WAS. I BELIEVE IT IS ALSO STENTON TAVERN. THE DEPLOYRABLES HANGOUT OF THE TIMES. ICE AGENTS AT HAND. GO GET UM-JUST SEND IT

Men's Race

2nd Place Team – Team America, 2nd Place Male – Austin Azar, 2nd Place Female – Suzanne Kraus

The men's race this year was full of ups and downs. Many lead changes happened throughout the race. Junyong Pak held an early lead followed by Nickademus Hollon, the blistering pace. Pak was the first to halter having trouble once again with keeping his body temperature warm and was medically pulled at night. Hollon took and extended break then finished his last lap in the morning calling his race at 75 miles.

As some athletes fell off the leaderboard others rose to the occasion. Trevor Cichosz continued to work his way up the leaderboard until he was in first place and would stay there for the rest of the race. At one point it looked like he ceded the race to the eventual second place finisher, Austin Azar. Azar also continued to creep up the leaderboard throughout the race and put everything he had into the race also crossing the 100-mile mark. In third place was Kris Mendoza who held strong the entire race and would also put in 100 miles on the course. Prior to this event, only one person had reached the 100-mile achievement and that was Ryan Atkins in New Jersey.

2016 WTM Men's Race Results

REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.Vol. 1, Thomas Lynch Montgomery, 1916,Contributed for use in the USGenWeb Archives by Georgette Ochs.Transcription is verbatim.

Indian Outbreak of 1763.Pg. 164-174.

Between the years 1759 and 1763 there was somewhat of a lull in the continued frequency of Indian atrocities. Then came the peace with the savages, and immediately followed the short and bloody outbreak called Pontiac's War, which, in 1764, finally closed the history of Indian Massacre in eastern Pennsylvania. Indeed, even during the years 1763-64 the territory of which I am treating, between the Susquehanna and Delaware Rivers, south of the Blue Mountains, saw little of the effects of this war, and so few incidents are recorded in comparison with the terrible events of previous years, that its treatise as a separate article, would hardly be warranted were it not for the occurrences which took place along the Lehigh River. Because they did occur in the immediate neighborhood about which I have just been writing, and because they treat so prominently of the Wetterholt brothers, I have deemed it best to take up the subject at this point, and so make a more or less consecutive narrative.

Through the kindness of Miss Minnie F. Mickley, of Mickleys, PA, I have furnished with a sketch, written by her father, Jos. J. Mickley, Esq., in 1875, entitled a "Brief Account of Murders by the Indians, and the cause thereof, in Northampton County, Penna., October 8th, 1763," from which I have taken the liberty of making many extracts, because of the complete manner in which his subject is treated.

I have said that, with the exception of what is about to follow, Eastern Pennsylvania was comparatively free from Indian massacres during 1763-64. This, in itself, would indicate a special reason for their occurrences removed from that which brought about the general hostilities. Such was actually the case. In "Heckewelder's account of the Indian Nations," p. 332, he says:

"In the summer of the year 1763, some friendly Indians from a distant place came to Bethlehem to dispose of their peltry for manufactured goods and necessary implements of husbandry. Returning home well satisfied, they put up the first night at a tavern (John Stenton's) eight miles distant from Bethlehem. The landlord not being at home, his wife took the liberty of encouraging the people who frequented her house for the sake of drinking, to abuse those Indians, adding, "that she would freely give a gallon of rum to any one of them that would kill one of these black devils." Other white people from the neighborhood came in during the night, who also drank freely, made a great deal of noise, and increased the fears of those poor Indians, who"for the greatest part understood English,"could not but suspect something bad was intended against their persons. They were, however, not otherwise disturbed; but in the morning, when after a restless night they were preparing to set off, they found themselves robbed of some of their most valuable articles they had purchased, and on mentioning this to a man who appeared to be the bar-keeper, they were ordered to leave the house. Not being willing to lose so much property, they retired to some distance in the woods, when some of them remaining with what was left them, the others returned to Bethlehem and lodged their complaint with a justice of the peace. The magistrate gave them a letter to the landlord, pressing him without delay to restore to the Indians the goods that had been taken from them. But, behold! When they delivered the letter to the people of the inn, they were told in answer, that if they set any value on their lives they must make off with themselves immediately. They well understood that they had no other alternative, and prudently departed without having received back any of their goods. Arrived at Nescopeck, on the Susquehanna, they fell in with some other Delaware Indians, who had been treated much in the same manner, one of them having his rifle stolen from him. Here two parties agreed to take revenge in their own way for those insults and robberies for which they could obtain no redress, and this they determined to do as soon as war should be again declared by their nation against the English."

As proof of the truth of this narrative Heckewelder added a note, "This relation is Authentic. I have received it from the mouth of the chief of the injured party, and his statement was confirmed by communications made at the time by two respectable magistrates of the county. Justice Geiger's letter to Tim. Horsfield proves this fact."

It might be interesting to add that the Rev. John Heckewelder was born in Bedford, England, March 12th, 1743. He came to America, with his parents, when quite young; during forty years was a missionary among the Indians in different parts of this country, exposed to many hardships and perils. He wrote several works on the Indians, which are instructive and interesting on account of his having been familiar with their language, manners and customs. He died at Bethlehem January 21st, 1823.

About the same time as this unfortunate occurrence, another one of similar character took place, which is given in Loskiel's "History of the Missions of the Indians in America," as follows:

"In August, 1763, Zachary and his wife, who had left the congregation in Wechquetank- on Poca-poca (Head's) Creek, north of the Blue Mountain, settled by Moravian Indians - (where they had belonged, but left some time previous), came on a visit, and did all in their power to disquiet the minds of the brethren respecting the intentions of the white people. A woman called Zippora was persuaded to follow them. On their return they stayed at the Buchkabuchka (this is the name the Munseys have for the Lehigh Water Gap - it means "mountains butting opposite each other") over night, where Captain Nicholas Wetterholt lay with a company of soldiers, and went unconcerned to sleep in ahayloft. But in the night they were surprised by the soldiers. Zippora was thrown down upon the threshing floor and killed; Zachary escaped out of the house, but was pursued, and with his wife and little child put to the sword, although the mother begged for their lives upon her knees."

The presence of Capt. Wetterholt at Lehigh Gap was probably owing to the fact that he was on his way either to or from Fort Allen, at Weissport, where a body of soldiers under his command, was still stationed. His Lieutenant at this time was a man named Jonathan Dodge, who seems to have been a most precious scoundrel. He had been sent from Philadelphia by Richard Hockley to Lt. Col. Timothy Horsfield, with a letter dated July 14th, 1763, recommending him as "very necessary for the service," and had been assigned by the latter to Capt. Wetterholt's company. It might be well to explain here that Timothy Horsfield, whose name appears frequently, was born April, 1708, in Liverpool, England. He emigrated to America, and settled on Long Island, in 1725; moved to Bethlehem in 1749; was appointed Justice of the Peace for Northampton County in May, 1752; commissioned Lieutenant-Colonel, and, as such, had the superintendence and direction of the two military companies commanded by the two Captains Wetterholt, which were ranging along the frontier; they sent their reports to him, and he corresponded with the Government at Philadelphia. Mr. Horsfield was of great service to the Government, as well as to the frontier inhabitants. He resigned both offices in December, 1763, and died at Bethlehem, March 9th, 1773.

Dodge committed many atrocious acts against his fellow soldiers, also against the inhabitants of Northampton County, but particularly against the Indians.

In a letter to Timothy Horsfield, dated August 4th, 1763, Dodge writes:

"Yesterday there were four Indians came to Ensign Kern's (where Worthington now is). * * * * I took four rifles and fourteen deer-skins from them, weighed them, and there was thirty-one pounds." After the Indians had left him, he continues: "I took twenty men and pursued them, * * * * then I ordered my men to fire, upon which I fired a volley on them, * * * * could find none dead or alive."

These were friendly, inoffensive Indians, who had come from Shamokin (Sunbury) on their way to Bethlehem.

Jacob Warner, a soldier in Nicholas Wetterholt's company, made the following statement September 9th: That he and Dodge were searching for a lost gun, when, about two miles above Fort Allen, they saw three Indians painted black. Dodge fired upon them and killed one; Warner also fired upon them, and thinks he wounded another; but two escaped; the Indians had not fired at them. The Indian was scalped, and, on the 24th, Dodge sent Warner with the scalp to a person in Philadelphia, who gave him eight dollars for it. These were also friendly Indians.

On the 4th of October, Dodge was charged with disabling Peter Frantz, a soldier; for striking him with a gun, and ordering his men to lay down their arms if the Captain should blame him about the scalp.

In a letter of this date Capt. Nicholas Wetterholt wrote to Timothy Horsfield: "If he (Dodge) is to remain in the company, not one man will remain. I never had so much trouble and uneasiness as I have had these few weeks; and if he continues in the service any longer, I don't propose to stay any longer. I intend to confine him only for this crime."

All this was at a time when, after years of warfare and murder, peace had just been concluded with the Indians, who seemed to be inclined to fully accept its terms. Care and good treatment of them were matters of great moment. The ill-timed and barbarous actions of Dodge, who was a bully and coward, execrated alike by his fellow soldiers and the Indians, had, therefore, much to do with bringing on the sad events which presently followed.

On October 5th, Capt. Nicholas Wetterholt place Lieut. Jonathan Dodge under arrest "for striking and abusing Peter Frantz," and sent him in charge of Captain Jacob Wetterholt, Sergeant Lawrence McGuire, and some soldiers to Timothy Horsfield at Bethlehem. We are not informed as to the result of his trial. His punishment could not have been much more than a reprimand, because he immediately started back for Fort Allen with Capt. Jacob Wetterholt. It would look as if Mr. Horsfield hesitated to give him a severe punishment because of influential friends, or connections.

On the 7th of October, Captain Jacob Wetterholt, with his party, left Bethlehem, on their way to Fort Allen. That same evening they arrived at John Stenton's tavern and lodged for the night. Being, so to say, in time of peace, when no danger of an Indian attack was apprehended, they did not deem it necessary to place sentrys about the building. To be sure, Capt. Wetterholt must have been aware of the treatment recently accorded the Indians at this very same place and might have thought that the presence of Dodge at this time, in this very building, would be a double incentive for the savages to wreak their vengeance, yet he had no reason to suspect their presence, and from his daring nature was inclined to look lightly on danger, so he neglected an ordinary precaution and violated a common military rule in not stationing guards.

During the night, the Indians, unperceived and unsuspected, approached the house. What happened, at break of day on October 8thy, is related as follows in Gordon's History of Pennsylvania:

"The Capt. designing early in the morning to proceed for the fort, ordered a servant out to get his horse ready, who was immediately shot down by the enemy; upon the Captain going to the door he was also mortally wounded, and a sergeant, who attempted to draw the Captain in, was also dangerously hurt. The lieutenant then advanced, when an Indian jumping on the bodies of the two others, presented a pistol to his breast, which he putting aside, it went off over his shoulder, whereby he got the Indian out of the house and shut the door. The Indians then went around to a window, and, as Stenton was getting out of bed, shot him; but, rushing from the house, he was able to run a mile before he dropped dead. His wife and two children ran to the cellar; they were fired upon three times, but escaped uninjured. Capt. Wetterholt, notwithstanding his wound, crawled to a window, whence he killed one of the Indians, who were setting fire to the house; the others then ran off, bearing with them their dead companion."

This description was taken from a detailed account sent by Mr. Horsfield with a messenger (John Bacher, who was paid for this service Oct. 12, £2 10s 4d. to the Governor, at Philadelphia. It was published in the Pennsylvania Gazette of October 13th, 1763, printed by Benjamin Franklin, also in the Philadelphische Staats-bote, printed by Heinrich Miller, in the German language, of October 17th, 1763.

The wounded were taken to Bethlehem, where Captain Wetterholt died the next day, at the Crown Inn, and so passed away a brave and energetic officer who deserved a better fate.

The effect upon our redoubtable Lieutenant Dodge was of a rather demoralizing character, if we may judge by his letter to Timothy Horsfield:

"John Stenton's, Oct. the 8, 1763.

Mr Horsfield, Sir, Pray send me help for all my men are killed but one, and Capt'n Wetterhold is almost dead, he is shot through the body, for god sake send me help.

These from me to serve my country and king so long as I live.

Send me help or I am a dead man.

This from me Ly'n't Dodge

sarg't meguire is shot through the body -

Pray send up the Doctor for god sake."

He evidently was of the class of men who spell God with a little "g" and his own name with a big "D", but in time of danger is anxious enough to call on the former for help, knowing how little reliance he can place on the latter.

Mr Horsfield, besides forwarding his report to the Governor, at once sent an express to Daniel Hunsicker, Lieutenant in Captain Jacob Wetterhold's company, with the following letter, to inform him of this disaster:

Bethlehem, Oct. 9, 1763

Sir: This morning at about break of day, a number of Indians attacked the inhabitants of Allen's Town (Allen Township); have killed several, and wounded many more. Your Captain, who was here yesterday, lays at the house of John Stenton, at Allen's Town, wounded. Several of the soldiers have been killed. I send to Simon Heller, and request him to send a safe hand with it, that you may receive it as quick as possible. Now is the time for you and the men to exert yourselves in defence of the frontier, which I doubt not you will do. I expect to hear from you when you have any news of importance. Send one of your worst men; as it will be dangerous in the day time, send him in the night. The enclosed letter to Mr. Grube (Rev. B. D. Grube, a Moravian Missionary at Wechquetank) I desire you send as soon as possible.

I am &c., TIMOTHY HORSFIELD.

To Lieutenant Hunsicker, Lower Smithfield.

This, however, was not the only mischief done by the Indians. They had come to avenge themselves on those who had ill-treated them, but, unfortunately, their savage nature once aroused, and excited by the first taste of blood, they continued their work of death throughout the whole neighborhood, sparing neither friend nor foe, slaying those who had abused them as well as those who had shown them many continued acts of kindness, until obliged to retreat. The missionary Heckewelder in his Account of the Indian Nations, p. 334, endeavors to palliate their crime by saying that the murder of the innocent people was owing to a mistake on the part of the savages. He remarks that "The Indians, after leaving this house (Stenton's) murdered by accident an innocent family, having mistaken the house they meant to attack; after which they returned to their homes." It was generally believed that they mistook this house for that of Paulus Balliet, which they intended to attack. Mr. Bailliet lived at the place now Ballietsville, and kept a store and tavern, similar to that of John Stenton.

Whatever may have been the explanation, the terrible fact still remains. The following account is given in the Pennsylvania Gazette, being an extract from a letter from Bethlehem, dated October 9:

"Early this morning came Nicholas Marks, of Whitehall Township, and brought the following account, viz:

That yesterday, just after dinner, as he opened his door, he saw an Indian standing about two poles from the house, who endeavored to shoot at him; but, Marks shutting the door immediately, the fellow slipped into a cellar, close to the house. After this said Marks went out of the house, with his wife and an apprentice boy. [This apprentice boy was the late George Graff, of Allentown, then fifteen years of age. He ran to Philip Jacob Schreiber with the news of these murders. He was Captain of a company in the Revolutionary War. In 1786 he resigned as Collector of the Excise, and was Sheriff of Northampton County in the years 1787-88-89. For three years he was a member of the Legislature, then holding its sessions in Philadelphia, from Dec. 3, 1793, to Dec., 1796. He lived many years in Allentown, where he died in 1835, in the 88th year of his age,] in order to make their escape, and saw another Indian standing behind a tree, who tried also to shoot at them, but his gun missed fire. They then saw the third Indian running through the orchard; upon which they made the best of their way, about two miles off, to Adam Deshler's place, where twenty men in arms were assembled, who went first to the house of John Jacob Mickley, where they found a boy and girl lying dead, and the girl scalped. From thence they went to Hans Schneider's and said Mark's plantations, and found both houses on fire, and a horse tied to the bushes. They also found said Schneider, his wife, and three children, dead in the field, the man and woman scalped; and, on going farther, they found two others wounded, one of whom was scalped. After this they returned with two wounded girls to Adam Deshler's and saw a woman, Jacob Alleman's wife, with a child, lying dead in the road and scalped. The number of Indains they think was about fifteen, or twenty.

I cannot describe the deplorable condition this poor country is in: most of the inhabitants of Allen's Town and other places are fled from their habitations. Many are in Bethlehem, and other places of the Brethren, and others farther down the Country. I cannot ascertain the number killed, but think it exceeds twenty. The people of Nazareth, and other places belonging to the Brethren have put themselves in the best posture of defence they can; they keep a strong watch every night, and hope, by the blessing of God, if they are attacked, to make a good stand."

"In a letter from the same county, of the 10th instant, the number killed is said to be twenty-three, besides a great many dangerously wounded; that the inhabitants are in the utmost distress and confusion, flying from their places, some of them with hardly sufficient to cover themselves, and that it was to be feared there were many house, &c., burned, and lives lost that were not then known. And by a gentleman from the same quarter we are informed that it was reported, when he came away, that Yost's mill, about eleven miles from Bethlehem, was destroyed, and all the people that belonged to it, excepting a young man, cut off."

After the deplorable disaster at Stenton's house, the Indians plundered James Allen's house, as short distance off; after which they attacked Andrew Hazlet's house, half a mile from Allen's, where they shot and scalped a man. Hazlet attempted to fire on the Indians, but missed, and he was shot himself, which his wife, some distance off, saw. She ran off with two children, but was pursued and overtaken by the Indians, who caught and tomahawked her and the children in a dreadful manner; yet she and one of the children lived until four days after, and the other child recovered. Hazlet's house was plundered. About a quarter of a mile from there the Indians burned down Kratzer's house, probably after having plundered it. Then a party of Indians proceeded to a place on the Lehigh, a short distance above Siegfried's Bridge, [Note: Cementon is located in the northwestern part of Whitehall Township, Lehigh Co., PA, along the west side of the Lehigh River. The town of Northampton, in Northampton Co., PA, is across the Lehigh River from Cementon. A ferry was originally established there some time around 1760. Later is was called Siegfried's Ferry, after Colonel John Siegfried, who kept a tavern on the Northampton Co. side. The actual bridge was erected in 1828, and then called Siegfried's Bridge. From Lehigh County History, v. I, page 1016. This is about a mile "up river" from Coplay.] to this day known as the "Indian Fall" or Rapids, where twelve Indians were seen wading across the river by Ulrich Schowalter, who then lived on the place now owned by Peter Troxel. Schowalter was at that time working on the roof of a building, the site of which being considerably elevated above the river Lehigh, he had a good opportunity to see and count the Indians, who, after having crossed the river, landed near Leisenring's Mountain. It is to be observed, that the greater part of this township, was at that time, still covered with dense forests, so that the Indians could go from one place to another almost in a straight line, through the woods, without being seen. It is not known that they were seen by any one but Schowalter, until they reached the farm of John Jacob Mickley (the great grandfather of Mr. Jos. J. Mickley), where they encountered three of his children, two boys and a girl, in a field under a chestnut tree, gathering chestnuts. The children's ages were : Peter, eleven; Henry, nine; and Barbary, seven; who, on seeing the Indians, began to run away. The little girl was overtaken not far from the tree by an Indian, who knocked her down with tomahawk. Henry had reached the fence, and while in the act of climbing it, an Indian threw a tomahawk at his back, which, it is supposed instantly killed him. Both of these children were scalped. The little girl, in an insensible state, lived until the following morning. Peter, having reached the woods, hid himself between two large trees which were standing near together, and, surrounded by brushwood, he remained quietly concealed there, not daring to move for fear of being discovered, until he was sure the Indians had left. He was, however, not long confined there; for, when he heard the screams of the Schneider family, he knew that the Indians were at that place, and that his way was clear. He escaped unhurt, and ran with all his might, by way of Adam Deshler's to his brother, John Jacob Mickley, to whom he communicated the melancholy intelligence. From this time Peter lived a number of years with his brother John Jacob, after which he settled in Bucks county, where he died in the year 1827, at the age of seventy-five. One of his daughters, widow of the late Henry Statzel, informed Mr. Mickley, among other matters, of the fact, related by her father, that the Mickley family owned at that time a very large and ferocious dog, which had a particular antipathy to Indians, and it was believed by the family that it was owing to the dog the Indians did not make an attack on their house, and thus the destruction of their lives was prevented. John Jacob Mickley and Ulrich Flickinger, then on their way to Stenton's, being attracted by the screams of the Schneiders, hastened to the place where, a short time before, was peace and quietness, and saw the horrible mangled bodies of the dead and wounded, and the houses of Marks and Schneider in flames. The dead were buried on Schneider's farm.

Courses. Distances.

N. 34° W. 13 miles, 6 furlongs.

N. 19° W. 3 miles, 6 furlongs.

N. 37° W. 14 miles, 5 furlongs (to the Lehigh, 32^^ miles).

N. 66° W. 3 miles, 3 furlongs.

N. 31° W. 8 miles, 3 furlongs (end of the first day, 43^ miles).

N. 35° 30' W. 8 miles.

N. 30° W. 8 miles, 7 furlongs.

Total distance, 60 miles, 6 furlongs, or about 6oj4 miles.

The average direct course from end to end was N. 36° W., and the air-line distance 6oJ^ miles.*

THESE COMPASS READINGS ALONG WITH THE GPS MAP BELOW CLEARLY SHOW ROUTE ON MY ROAD-NOT ALONG CREEK IN WHICH HISTORIANS BELIEVE- ALSO- IN OTHER ACCOUNTS IT WAS MENTIONED AT THE END OF FIRST DAY THE SHERIFF INFORMED THE RUNNERS TO STEP IT UP A BIT AS TIME IS CLOSING AND THEY MUST CLIMB THE HILL!!!!! THE WINNER MARSHALL WAS EVEN NOTED AS GRASPING A SMALL SAPLING/TREE AT THE SUMMIT TO HOLD HIS BALANCE- HE WAS WIPED OUT. THEY RESTED AT THE TOPOF THE HILL AND PROBABLY MADE A FIRE FOR THE PEOPLE IN BETHLEHEM OR OTHER SIDE OF RIVER TO SEE IT. THEY PRACTICED THIS ROUTE SEVERAL TIMES -THE ENGLISH NEW EXACTLY WHERE THEY WERE GONNA CAMP THAT NIGHT.

'Other estimates varied all the way from 48 to 120 miles. To give their charges of fraud more weight, the Indians reckoned the distance as 80 miles. The achievement was remarkable enough, even accepting the con- servative and actual measurements made by Surveyor Eastburn; so there is no need to magnify the figures.

LARDNER FAMILY. The English family of Lardner, to which Lynford Lardner, Provincial Coun- cillor of Pennsylvania (1755-73) belonged, was one of the old famiHes of Nor- folk or Kent counties, and bore as its arms, "Gu. on a fesse between three boars' heads couped ar. a bar wavy sable." These arms were used as a seal by the Coun- cillor. His great-grandfather Lardner married a Miss Ferrars, and their son, Thomas Lardner, married and had issue: John Lardner, m. Miss Winstanley; of whom presently; James Lardner, distinguished clergyman ; Thomas Lardner ; Sarah Lardner, m. a Springett of Strumshaw, Norfolk. John Lardner, eldest son, father of Lynford Lardner, studied at Christ Col- lege, Cambridge, and received there the degree of Medical Doctor. He had a town house on Grace Church street, London, and a country house at Woodford, Epping Forest, county of Essex; had a good practice and reputation as a physi- cian, and was related to Most Rev. Dr. Thomas Herring, Lord Archbishop of Canterbury. John Lardner had issue: Francis Lardner, d. June 18, 1774; bur. St. Clement's, London; John Lardner, d. 1740-1 ; Hannah Lardner, m. Richard, son of William Penn, the Founder, and one oi the Pro- prietaries of Pa.; Thomas Lardner, citizen of London; Lynford Lardner, the Councillor; of whom presently; James Lardner, of Norwich, county Norfolk; Elizabeth Lardner, m. Wells, of county Norfolk. Lynford Lardner, born near London, England, July 18, 171 5, was named for a near relative and friend of the family, Rev. Thomas Lynford, S. T. D., Rector of St. Nicholas Aeon and Chaplain of King William and Queen Mary, and like his father was entered as a student at the Univerity of Cambridge, but later accepted a position in a counting-house in London. His family made an effort to secure him a government position in England, and failing, the influence of his brother-in-law, Richard Penn, secured him an opening in Pennsylvania, and he came to Philadelphia at the age of twenty-five years, sailing from Grave- send May 5, 1740, and arriving in Philadelphia in the beginning of September. He was at once employed in the land office, and assisted in the management of the wild and unsettled lands of the frontier then being rapidly opened up for settle- mnt under the purchase of 1736. August 8, 1741, he was appointed to succeed James Steel as Receiver-General of the Province, and had charge of the collec- tion of the Quit Rents and purchase money due the Proprietaries, as well as act- ing as their commercial agent, in which position he displayed excellent business ability. He was made Keeper of the Seal, December 12, 1746, and held that posi- tion and the office of Receiver-General until March 28, 1753, being succeeded in 926 LARDNER both positions by Richard Hockley, a protege of John Penn, another of the Pro- prietaries. His association with the land ofifice gave him the opportunity to secure grants of valuable lands in his own right and he became a large landed proprietor. As early as 1746, he became the owner of Collady's Paper Mills, Springfield town- ship, Chester (now Delaware) county, and soon after that date he was largely interested in the manufacture of iron in Berks and Lancaster counties. He be- came a Justice of Lancaster County Courts October 16, 1752. His connection with the Penn family gave him a position in the social and business world of Philadelphia which his eminent ability easily qualified him to fill. He was named as one of the directors of the Library Company, of Philadelphia, 1746, and again 1760, and was an original manager of the Dancing Assembly, instituted in the winter of 1748. He was called to the Provincial Council June 13, 1755, and con- tinued a member of that body until his death. The Assembly having made no provision for the raising of troops for the defense of the frontiers, the people of the various counties of the state raised volunteer companies called associators, and elected 'their officers. Lynford Lardner volunteered in the first company of the Philadelphia Associators, was elected First Lieutenant, and with the regi- mental officers of the Philadelphia Regiment, was commissioned by the Provincial Council January 28, 1747; again, March, 1756, he was commissioned Lieutenant of the Troop of Horse organized by the Council with two companies of foot and one of artillery, for the defense of the City of Philadelphia in the French and Indian War. He was also named as one of the commissioners to disburse the money appropriated by the Assembly "for the King's use." He was one of the trustees of the College of Philadelphia, parent of the University of Pennsylvania, and a member of the American Philosophical Society. October 27, 1749, he married Elizabeth, born in Philadelphia, 1732, daughter of William Branson, a wealthy merchant in Philadelphia, and sister to the wife of Richard Hockley, who succeed- ed him as Register-General and Keeper of the Seal. After his marriage he resid- ed on the west side of Second street, above Arch, and had his country seat, "Som- erset," on the Delaware, near Tacony, part of which has since been known as Lardner's Point. He owned a number of stores and houses in the vicinity of his residence and a large amount of real estate in the upper part of the city. Over 2500 acres of land were surveyed to him in Bucks county, 1741-51, most of it lying in what became Northampton county, 1752. On a tract of several hundred acres in Whitehall township he erected a commodious building which he named "Grouse Hall," where he and a number of his Philadelphia friends were in the habit of sojourning to shoot grouse and other game abundant in that locality. The "Hall" being painted white, and known by travelers and inhabitants as "the White Hall," is said to have given the name to the township when organized in 1753. Mr. Lardner secured warrants of survey for over 5000 acres of land in Northampton county after its organization. He was a keen sportsman, exceed- ingly fond of outdoor life, and doubtless spent much time in company with his friends upon his wild land in Northampton county, he was also a member of the Gloucester Fox Hunting Club. He died October 6, 1774, and was buried at Christ Church. His wife, Elizabeth Branson, died August 26, 1761, and he married (second) at Christ Church, May 29, 1766, Catharine Lawrence, who survived him.

THIS IS A FAKE NEWS EVENT. FOR ON OCTOBER 7 1763 THE KING OF ENGLAND DECLARES ALL INDIANS OUT OF THE TERRITORY TO LIVE ON A RESERVE, THE NEXT DAY THEY DID THIS TO INCITE THE EARLY AMERICANS TO VANQUISH ALL LENNI LENAPE INDIANS OUT.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on October 7, 1763, following Great Britain's acquisition of French territory in North America after the end of the French and Indian War and the Seven Years' War. This proclamation rendered all land grants given by the government to British subjects who fought for the Crown against France worthless. It forbade all settlement west of a line drawn along the Appalachian Mountains, which was delineated as an Indian Reserve.

The very next day October 8 is this fake news attack on Stenton tavern-its on lynford lardner land next to james allen(started Allentown)- the rich ones in charge did this to start the official slaughter campaign and rid the area of indians-william penn rolls over in the Quaker grave- all in the name of Jesus-but then again it was meant to be.

On October 9 lynford Lardner is noted in Queens book registrar in local government area(Philadelphia) by lardner himself to ask for funds and a militia to seek reprisal, fascinating this fake news bullshit

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on October 7, 1763, following Great Britain's acquisition of French territory in North America after the end of the French and Indian War and the Seven Years' War. This proclamation rendered all land grants given by the government to British subjects who fought for the Crown against France worthless. It forbade all settlement west of a line drawn along the Appalachian Mountains, which was delineated as an Indian Reserve.

The very next day October 8 is this fake news attack on Stenton tavern-its on lynford lardner land next to james allen(started Allentown)- the rich ones in charge did this to start the official slaughter campaign and rid the area of indians-william penn rolls over in the Quaker grave- all in the name of Jesus-but then again it was meant to be.

On October 9 lynford Lardner is noted in Queens book registrar in local government area(Philadelphia) by lardner himself to ask for funds and a militia to seek reprisal, fascinating this fake news bullshit

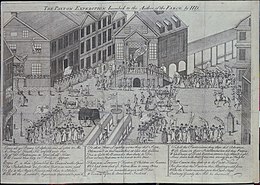

Paxton Boys

The Paxton Boys were frontiersman of Scottish Ulster Protestants origin from along the Susquehanna River in central Pennsylvania who formed a vigilante group to retaliate in 1763 against local American Indians in the aftermath of the French and Indian War and Pontiac's War. They are widely known for murdering 20 Susquehannock in events collectively called the Conestoga Massacre.

Following attacks on the Conestoga, in January 1764 about 250 Paxton Boys marched to Philadelphia to present their grievances to the legislature. Met by leaders in Germantown, they agreed to disperse on the promise by Benjamin Franklin that their issues would be considered.

Attack on Susquehannock[edit]

In the aftermath of the French and Indian War, no Europeans had yet settled in the frontier of Pennsylvania. A new wave of Scots-Irish immigrants encroached on Native American land in the backcountry often in blatant violation of previously signed treaties. These settlers claimed that Indians often raided their homes, killing men, women and children. Reverend John Elder, who was the parson at Paxtang, became a leader of the settlers. He was known as the "Fighting Parson" and kept his rifle in the pulpit while he delivered his sermons.[1] Elder helped organize the settlers into a mounted militia and was named captain of the group, known as the "Pextony boys."[2]

Although there had been no Indian attacks in the area, the Paxton Boys claimed that the Conestoga secretly provided aid and intelligence to the hostiles. At daybreak on December 14, 1763, a vigilante group of the Scots-Irish frontiersmen attacked Conestoga homes at Conestoga Town (near present-day Millersville), murdered six, and burned their cabins.

The Susquehannock tribe had lived on the land which was ceded by William Penn to their ancestors in the 1690s. Many Conestoga were Christian, and they had lived peacefully with their European neighbors for decades. They lived by bartering handicrafts, hunting, and from subsistence food given them by the Pennsylvania government. Because of a snowstorm, most of the Conestogas had been unable to reach home the previous evening and spent the night with neighbors. Those at the camp were scalped, or otherwise mutilated, and their huts were set on fire. Most of the camp burned down.[3]

The colonial government held an inquest and determined that the killings were murder. The new governor, John Penn offered a reward for capture of the Paxton Boys. Penn placed the remaining sixteen Conestoga in protective custody in Lancaster but the Paxton Boys broke in on December 27, 1763. They killed, scalped and dismembered six adults and eight children. The government of Pennsylvania offered a new reward after this second attack, this time $600, for the capture of anyone involved. The attackers were never identified.

The Rev. Elder, who was not directly implicated in either attack, wrote to Governor Penn, on January 27, 1764:

March on Philadelphia[edit]

In January 1764, the Paxton Boys marched toward Philadelphia with about 250 men to challenge the government for failing to protect them. Benjamin Franklin led a group of civic leaders to meet them in Germantown, then a separate settlement northwest of the city, and hear their grievances. After the leaders agreed to read the men's pamphlet of issues before the colonial legislature, the mob agreed to disperse.

Many colonists were outraged about the December killings of innocent Conestoga, describing the murders as more savage than those committed by Indians. Benjamin Franklin's "Narrative of the Late Massacres" concluded with noting that the Conestoga would have been safe among any other people on earth, no matter how primitive, except "'white savages' from Peckstang and Donegall!"[5]

Lazarus Stewart, a former leader of the Paxton Boys, was killed by Iroquois warriors in the Wyoming Massacre in 1778 during the American Revolutionary War.[6] In the Wyoming Valley event, one of three famous massacres during many scattered Tory-Amerindian staged attacks on colonial settlements that year in Connecticut, New York and Pennsylvania, Mohawk chief Joseph Brant led a group of Loyalists, Mohawk and other warriors against rebel colonial settlers in the area along the North Branch Susquehanna River. The raids resulted in the Sullivan Expedition the next year which effectively broke the power of the Six Nations of the Iroquois below Canada; and forced the British Colonial powers in Canada to shelter the Amerindians they'd incited into the attacks.